Mechanical ventilation (aka assisted ventilation) is the medical term for artificial ventilation in which mechanical means are used to assist or replace breathing. Mechanical ventilators can be used in invasive mode, where an endotracheal tube is inserted through the mouth into the patient’s trachea (windpipe). Invasive ventilation could be used during an acute respiratory failure or a surgery where the patient is unable to manage breathing. Figure 1 shows this mode of mechanical ventilator.

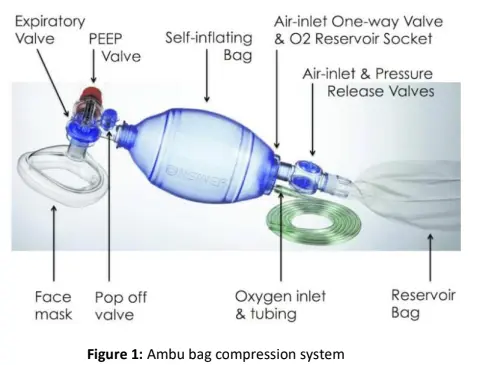

Non-invasive ventilation uses a mask over a patient’s mouth and nose. In its simplest form, the Ambu bag compression system consists of a flexible bag mask, ventilation tubing, valves, an oxygen tube, a reservoir bag, and a face mask. The bag mask can be compressed by a person or by mechanical means. Figure 2 shows the scenario

Mechanical ventilators are widely used for patients who are suffering from ARDS (Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome). With the COVID-19 pandemic spreading worldwide and its flu-like symptoms similar to those of ARDS, the burning question is whether there are enough mechanical ventilators to support patients with ARDS. One study by Johns Hopkins University (Reference 1) estimates that there are 160,000 mechanical ventilators in use. 62,000 are full-featured, and the remaining 98,000 units, although not fully equipped, meet the basic needs of a patient with ARDS. In a pandemic emergency such as COVID-19, there may be a 25% surge in the demand for ventilators (Reference 1). If the pandemic follows the pattern of the Spanish Flu of 1918, approximately 740,000 ventilators will be required (Reference 2).

Mechanical ventilators are widely used for patients who are suffering from ARDS (Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome). With the COVID-19 pandemic spreading worldwide and its flu-like symptoms similar to those of ARDS, the burning question is whether there are enough mechanical ventilators to support patients with ARDS. One study by Johns Hopkins University (Reference 1) estimates that there are 160,000 mechanical ventilators in use. 62,000 are full-featured, and the remaining 98,000 units, although not fully equipped, meet the basic needs of a patient with ARDS. In a pandemic emergency such as COVID-19, there may be a 25% surge in the demand for ventilators (Reference 1). If the pandemic follows the pattern of the Spanish Flu of 1918, approximately 740,000 ventilators will be required (Reference 2).

In the case of a severe pandemic, medical staff may not be available to use the Ambu bag. For greater simplicity, a mechanical design that uses a stepper motor can be used to periodically squeeze the bag to deliver a specific volume of oxygen. Several designs have been proposed (References 3, 4, 5) with the two essential parameters of the design being the speed of the motor (which controls the pumping rate) and how much the bag mask is squeezed, which depends on the motor torque and the positioning of the bag mask with respect to the squeezing arm.

The more sophisticated mechanical ventilators have several modes of operation, such as Volume Control Ventilation (VCV), Pressure Control Ventilation (PCV), Synchronized Intermittent Mandatory Ventilation (SIMV), Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP), Pressure Support Ventilation (PSV), etc. One such unit is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: A more equipped mechanical ventilator

The most recent machines have many features, such as LCD or CRT waveform displays, calculated lung mechanics, and system diagnostics. A few important parameters for mechanical ventilators need to be described. They are:

- Tidal Volume: The volume of air into and out of the lungs during each ventilation cycle, shown in Figure 4 (Reference 6). It is usually in the 400-500 ml range.

Figure 4: Tidal volume is shown on the graph

- I:E ratio: The Inhale to Exhale ratio refers to inspiratory time to expiratory time. In normal spontaneous breathing, this ratio is about 1:2, but in patients with ARDS it should be about 1:2.7, although it also depends on lung condition. The total range is 1:2 to 1:4.

- Pressure: It is essential to monitor peak and plateau pressures during mechanical ventilation. As the tidal volume increases, so does the pressure to force that volume into the lungs. Pressure is measured in units of cm H2O and is usually between 20 and 30 cm H2O.

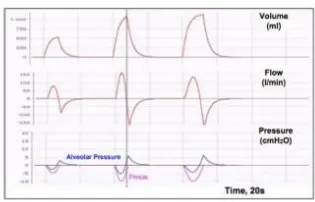

The tidal volume, flow, and lung pressure, whether spontaneous or assisted by mechanical ventilation, can be depicted using diagrams. Figure 5 shows the spontaneous breathing parameters plotted over time (Reference 7). One can see that the tidal volume (top red curve) varies with each cycle, and the flow rate (middle red curve) is adjusted to support it. The muscular lung pressure (Bottom pink curve) is negative during inhalation and zero during exhalation. The alveolar pressure (Blue curve) follows the lung muscular pressure during inhalation and becomes positive during exhalation.

Figure 5: Spontaneous breathing

In a controlled cycle, where the mechanical ventilator controls the entire respiratory cycle, one can fix the volume (VCV, or Volume-Controlled Ventilation). The performance of the breathing cycle is then depicted in Figure 6 (Reference 7).

Figure 6: VCV mode for a controlled cycle

In this case, the tidal volume (top red curve) was constant, but the inspiratory flow (Middle red curve) changed in each cycle, resulting in different times and inspiratory airway pressures (Bottom red curve). Muscular pressure is zero because the patient shows no respiratory effort during a controlled cycle. Finally, the alveolar pressure (Blue curve) did not change because the tidal volume determined it.

References

1. Ventilator stockpiling and availability in the US, Johns Hopkins, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Feb 4, 2020.

2. The New York Times online article by Aaron Carroll,

3. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1t2t8d8xtD0

4. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oLQ5bXakWq8

5. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DdQg11QgpXg

6. Respiratory volumes and lung capacity explained. Online resource. TeachPE.com

7. Basis modes of mechanical ventilation, Marcelo Alcantra Holanda, XLung online resource.